Chinese industry: towards a target for reducing CO2 emissions

China, the world’s leading industrial power, is now at a historic turning point. While the country’s meteoric industrial growth has long gone hand in hand with a steady rise in CO₂ emissions, recent data shows an unprecedented inflection point: for the first time, China has reduced its CO₂ emissions not because of an economic shock, but thanks to the rise of renewable energies. This development ushers in a new era for Chinese industry, marked by innovation, an upmarket technological edge and an accelerated ecological transition.

An unprecedented energy turning point

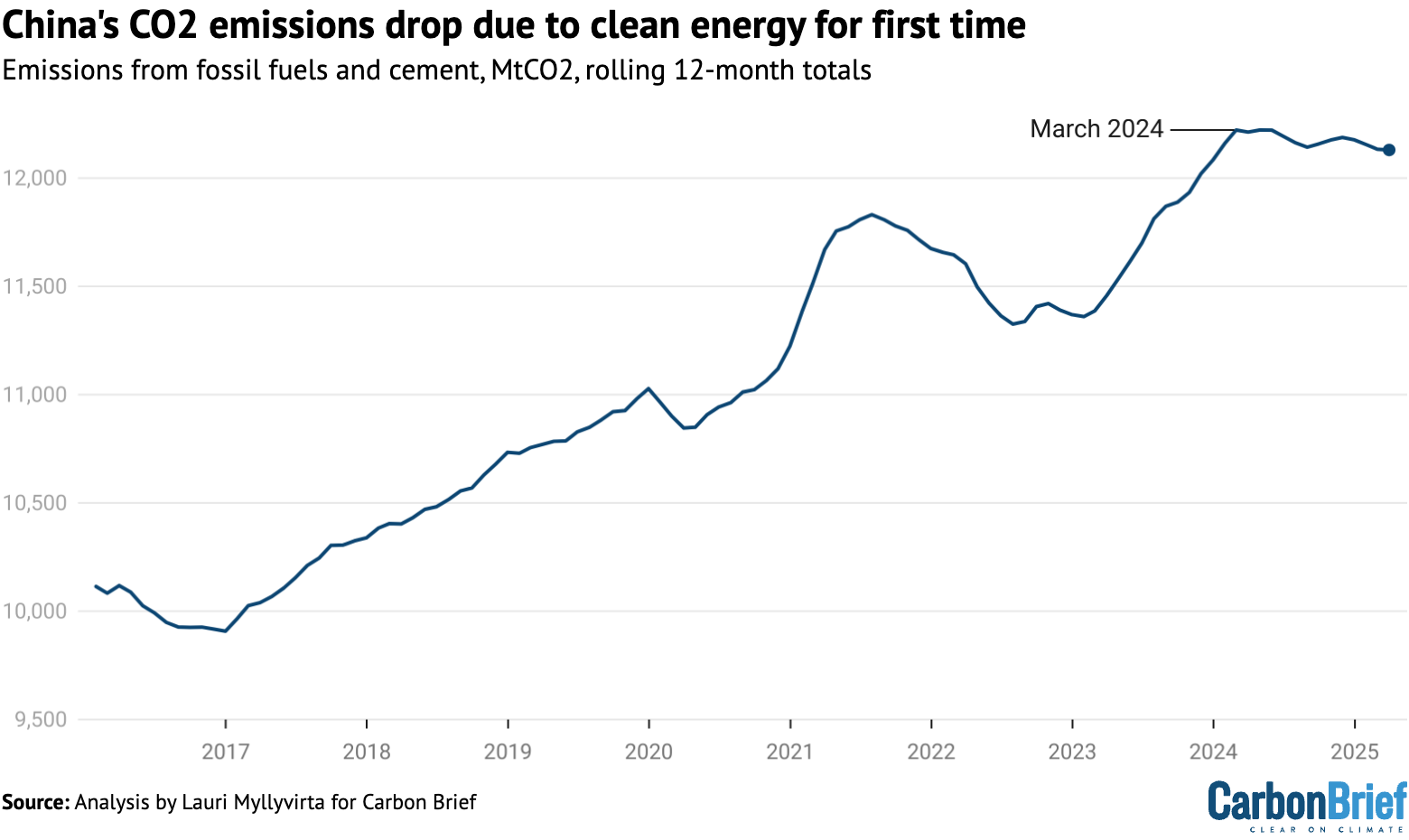

In the first quarter of 2025, China’s CO₂ emissions fell by 1.6% compared to the same period in 2024, with a 1% drop over the last twelve months according to a study conducted by the Clean Air and Energy Research Centre, published by specialist media outlet Carbon Brief.

This reduction is the direct result of record growth in solar, wind and nuclear power generation capacity. For the first time, the combined output of solar and wind power has overtaken that of hydroelectricity, reaching 951 TWh in the first quarter of 2025, an increase of 19% on the previous year. This performance is due to massive additions of renewable capacity: 23 GW of solar and 13 GW of wind were installed in March 2025 alone.

This energy shift has helped to reduce dependence on coal, despite energy demand rising by 2.5% in the first quarter of 2025. Thermal generation fell by 4.7% over the same period, illustrating the effectiveness of the transition. If this trend continues, it could herald a structural decline in emissions from China’s energy sector, the main source of the country’s emissions.

China’s changing industry

In 2024, China consolidated its position as the world’s leading manufacturing power, accounting for around 31.6% of global industrial output, according to a report published by Safeguard Global. But this quantitative supremacy has long masked a reality: lower productivity than in Western countries, an abundant, low-skilled workforce, and heavy dependence on exports. Today, Chinese industry is moving resolutely towards greater quality, innovation and sustainability, even if this shift raises major concerns, particularly about the social consequences of robotisation and the future of the low-skilled workforce.

This change is reflected in a number of key trends:

- Upmarket technology: China is investing massively in cutting-edge technologies, robotics, artificial intelligence, semiconductors and biotechnology. The ‘Made in China 2025’ programme aims to make China a world leader in these strategic sectors.

- Automation and Industry 4.0: Automation is transforming production lines, reducing reliance on low-skilled labour. Taiwanese giant Foxconn, for example, known for assembling Apple’s iPhones, has replaced more than 100,000 workers with robots in recent years.

- Relocation and diversification: Faced with rising labour costs and trade tensions, many foreign companies are diversifying their production into other countries (Vietnam, India, Mexico). Beijing is responding by strengthening its domestic market and encouraging local innovation.

- Investment in R&D: China devotes more than 2.68% of its GDP to research and development, a trend that has been rising since 2010 according to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Technology giants such as Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent (BAT) are at the heart of this dynamic.

Decarbonisation, a strategic lever

The energy transition is becoming a strategic lever for China. The world’s leading producer of solar panels, wind turbines and batteries for electric vehicles according to the International Energy Agency, the country has set itself ambitious targets of carbon neutrality by 2060, likely to transform its industry in depth.

The recent fall in CO₂ emissions is therefore the result of a proactive policy and massive investment in renewable energies. But decarbonisation does not just concern the energy sector: emissions from cement production have fallen by 28% since 2021, while oil product consumption has been on a downward trend since March 2024, thanks to the electrification of transport and the conversion of freight to liquefied natural gas.

However, this positive trend needs to be qualified. Some sectors, such as metallurgy and chemicals, saw their emissions increase by 3.5% in the first quarter of 2025, driven by a rebound in demand and favourable coal prices. The burgeoning sector of coal-to-chemicals conversion is also a concern, as it could slow overall progress.

In addition, the construction of coal-fired power stations continues, with new units being built in the east of the country, according to Global Energy Monitor. The dominance of so-called ‘green’ value chains also has negative consequences (massive and often polluting extraction of certain rare metals, outsourcing of certain ecological impacts to third countries, etc.).

The challenges and opportunities of industrial transition

China’s long-term trajectory will largely depend on the next five-year plan (2026-2030), which is supposed to set energy and climate objectives for 2030. To remain in line with its international commitments, China will have to significantly accelerate the reduction in the carbon intensity of its economy.

Global competition is based on several pillars: clean technologies, infrastructures and diplomatic influence. China’s mastery of the solar value chain and its cost-competitiveness make it a key player in the global energy transition. China’s rapid decarbonisation could thus become a major strategic lever in an increasingly polarised world.

Nevertheless, uncertainty remains. The new tariff regime for renewable electricity, due to come into force in June 2025, could cause cycles of instability in the sector, particularly for distributed photovoltaics. The official target of adding 200 GW in 2025 remains well below the 360 GW achieved in 2024, suggesting that the pace of the energy transition could slow down, at least temporarily. In addition, global geopolitical instability, trade tensions with the United States and commodity volatility could have a major impact on the pace of transition.

While China’s industrial and ecological transition is based on strong state planning, it also raises questions about governance, data transparency and the participation of local stakeholders. This centralised steering could limit democratic adjustments or public debate on technological choices and their social impacts, while concerns remain that this strategy may be more concerned with image than with structural transformation.

Conclusion: towards a new industrial model

The future of industry in China is taking shape under the banner of transformation. After decades of growth based on mass production and exports, China wants to embark on an ambitious ecological and technological transition. The recent fall in CO₂ emissions, driven by the rise of renewable energies, marks a real but fragile turning point, the future of which will depend on many parameters over the next few years… Beyond the quantified targets, achieving carbon neutrality remains an arduous challenge, with persistent challenges in certain industrial sectors as well as regulatory and institutional uncertainties, particularly over the governance of the transition process.

Source : les analyses du Centre de recherche sur l’énergie et l’air pur (Crea), publiées par Carbon Brief, et sur les données relatives à la transformation de l’industrie chinoise1.

IEA – International Energy Agency

More news News